The race of the races

Affirmative actions’ effects on higher education admissions for those of minority cultures

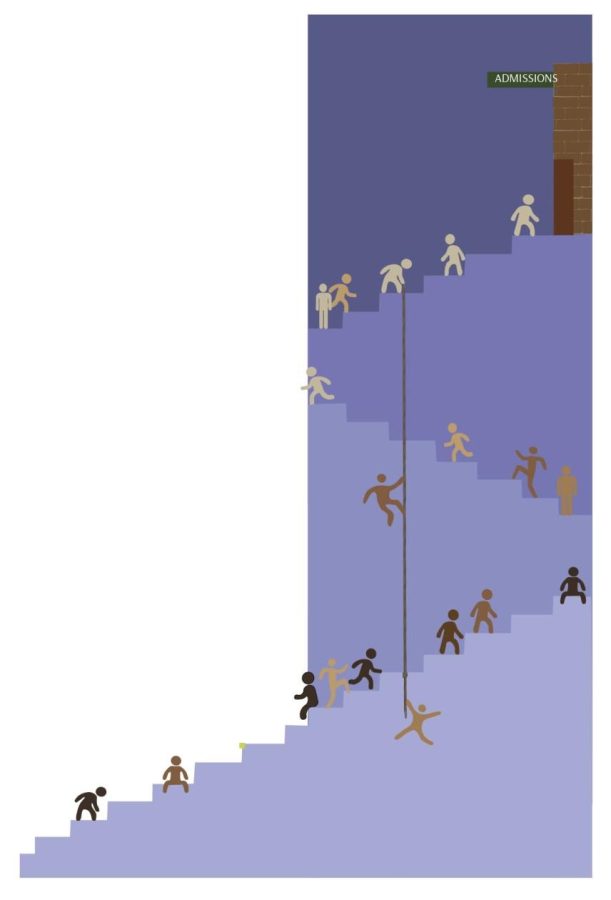

23% fewer students of color were admitted to highly selective schools after affirmative action was banned. 80% of all U.S college students were white in 1976. By 2016, that percentage has dropped to 57%.

June 7, 2022

Jane Doe keeps her head down as her college counselor questions her about her college plans.

“Jane? Are you there?” says the counselor.

The truth is, Jane has no college plans. She never expected to have the academic ability to go to college, nor the financial mobility. Jane’s parents immigrated to America a few months before she was born. They opened a small restaurant to support themselves, though the restaurant struggles at times, putting Jane’s family in a tight financial spot. Jane works at her parents’ restaurant every day of the week and weekends in order to help support her family. When she is not working, she takes care of her four younger siblings.

On top of her personal life, Jane is a senior at her local high school and attends classes five days a week, every week. Though she works hard in school and earns good grades, she has no time for extracurriculars, AP classes or any of the resume building activities her fellow students partake in due to her situation at home.

Jane’s counselor then introduced her to some college admissions programs and scholarships that help under-represented and low income students, it was then that she started considering pursuing a higher education. Maybe college could help not only her situation, but her family’s as well.

Though Jane Doe is not a real person, these are the circumstances for thousands of high school students who are applying to college around the United States. These programs and scholarships can be labeled as affirmative action, the effort to improve opportunities for members of minority groups. Affirmative action works in employment and government, but more controversially, education, specifically college admissions. As stated by Louis Menand in his article “The changing meaning of affirmative action,” the topic is vast with great depth, and can be hard to navigate.

With its benefits of diversifying student bodies and offering underrepresented students new opportunities, affirmative action is argued to undermine those who have earned a spot at colleges through merit, regardless of race and socioeconomic situation. Many do not know where they stand on this controversy because of morals belonging to both sides of the argument.

“I don’t fully support affirmative action because in an effort to correct past socioeconomic wrongs, a lot of people aren’t receiving the admissions and opportunities that they worked hard for,” senior Cristina Canepa said. “However, I also understand that it promotes diversity and provides equal opportunities for underrepresented people.”

In the argument against affirmative action being used in college admissions, it is said to be a form of reverse discrimination in which colleges admit students of color based on their race in the name of diversity. White individuals may feel colleges are excluding white students who have earned their spot through hard work and merit. The process can be perceived as discrimination against white students. Students like junior Abby Wile think reverse discrimination doesn’t exist.

“I don’t think reverse discrimination exists. Our society has deep-rooted systematic racism, allowing white privilege to remain prevalent,” junior Abby Wile said. “Affirmative action helps counter this in college admissions.”

In countering white privilege, affirmative action attempts to “level the playing field,” by ensuring that non-white individuals are given equal consideration and opportunities. When choosing between two admits, one white student and one non-white student with equal academic accomplishments, colleges may choose the non-white student in order to fit certain diversity requirements.

“Even though affirmative action can be unfair to white students when they have equal qualifications to someone admitted over them, many times there are more opportunities out there for them to pursue than students of color,” Canepa said. “It may be a little unfair, but in the big picture they historically have had more options.”

The historic exclusion of students of color is recalled when combating arguments of white exclusion, along with the extensive time it has taken to legally combat the exclusion of students of color. Affirmative action in it’s current form originated in the 1960’s.

According to Nicholas Lemann’s history of meritocracy, The Big Test, the man who coined the term was an African-American lawyer from Texas named Hobrat Taylor, Jr. He worked the flexible phrase into Lyndon B. Johnson’s original draft of what would become Executive Order 10925. President John F. Kennedy signed the order in 1961, requiring government contractors to “take affirmative action” to ensure that applicants are employed without regard to their race or national origin. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 followed, ending segregation in schools and opening a new chapter toward equality for all minorities. Ethnic studies and U.S. History teacher Carlen Floyd gives insight on how history influences present conflict.

“Historically, laws and policies have been created to benefit those in power,” Floyd said. “Referring to the ‘top choice’ spot being taken away from white people and given to those facing injustice through legislation. It is difficult for anyone to feel a shift in power, particularly in losses dealing with persecution, oppression and discrimination.”

Since those historical changes, diversity in higher education has risen. In 1976, white students made up 83 percent of all U.S. college students. That percentage dropped to 57 percent by 2016. Though many argue affirmative action in education should be directed more towards early stages of education, rather than a focus on admissions processes. Floyd gives insight on the financial impacts on education overall and as it relates to underrepresented populations.

“Particularly in Texas, education is being paid for by property taxes. It [school finance] is connected because we’re talking about access to education, access to the highest technology, access to the best teachers…there’s evidence today that there are populations that have not had access to the best,” Floyd said. “We need to take into consideration those issues when attempting to create a more diverse student population.”

A study done by The American Council on Education found that in the 2015-16 school year, 52 percent of undergraduate students identified as white. While only 19.8 percent of students identified as Hispanic or Latino and 15.2 percent identified as Black. The same year, The Pew Research Center found there were 20 million undergraduate students, meaning 10.4 million students identified as white.

“Schools that do have a high percentage of minorities are consistently underfunded or poorly managed,” senior Brandon Almaguer said. “A fair education system needs to take place while students are still young so that they are provided the resources necessary to thrive in a college setting.”

The advocation for affirmative action’s redirection to educational access at the grade school level bleeds into the support behind the merit principle. The logic being schools should take away race as a factor and solely focus on academic merit. Those who oppose affirmative action believe it undermines that principle because colleges seem to ignore the personal work put in by a student and judge them by their race, a factor they had no control over.

“Affirmative action may leave some kids wondering what the point of going above and beyond in high school [is] if their fate is ultimately determined by things other than their personal achievements,” Canepa said. “From that aspect, it can undermine the merit principle.”

Senior students of color feel their colleges cared more for their race than their academic achievement when accepting them.

“I’m Hispanic, and since schools have to meet certain diversity requirements, I felt like I was weighted more heavily on my ethnicity than my academic achievements or my extracurriculars,” Canepa said. “I felt like it reached a point where the qualifications didn’t matter, and it came down to whether they had fulfilled their ‘quota’ or not.”

Underrepresentation of certain races at universities leads to diversity factors increasing and their larger desire for said race.

“Affirmative action played a role in my acceptance since the college values diversity,” Almaguer said. “Hispanics are often underrepresented so I may have been favored over someone who was not Hispanic.”

With college’s specificity on the inclusion of certain minorities disregarding equal merit, they are also increasing diversity and desegregation.

“Without affirmative action, there may be a demographic shift in certain colleges,” Canepa said. “Many colleges would likely appear segregated in their represented population.”