Concerns over CRT impact classrooms

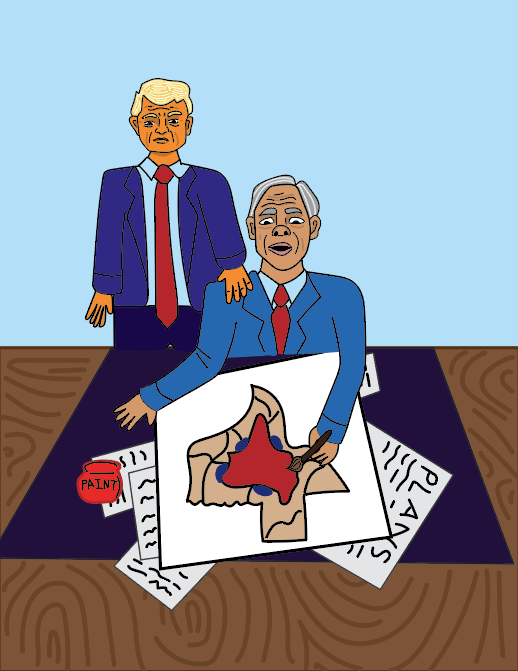

The bill was created in the Texas House and then sent to Greg Abbott to sign. There is also a Senate bill that is similar but goes beyond just history courses and would have similar restrictions on topics in all school courses.

November 16, 2021

History and humanities teachers struggle to balance their curriculum amid controversy

Over the summer of 2021, Greg Abbott signed House Bill 3979 which has been named the critical race theory (CRT) bill. This bill became law on Wednesday, Sept. 1, 2021. The CRT bill covers what teachers can and can not teach in history and current events. With it’s passing many conversations have been sparked as it limits how teachers can discuss current issues and how they go about discussing topics like race and identity.

According to Kimberlé Crenshaw, one of the originators of CRT, the phrase critical race theory is an academic term used for describing race and how racism has impacted social and local areas of the United States. The topic CRT covers a variety of topics and explains how race intertwines with identity and how racism impacts many areas of the United States.

“Critical race theory is definitely one of those really lofty academic critical lenses to examine policy and society and nothing I ever had the opportunity to learn about at the high school level,” humanities instructional coach Whitney Shumate said. “I think that it’s a really fascinating way to be able to think critically about our society and policies that we vote for and that affects us on a day to day basis.”

The bill prohibits lessons around current events from happening if a teacher does not show views from both sides without expressing any bias or leaning towards one of the opinions. The CRT bill also prohibits teachers from offering extra credit for students for volunteering or work affiliated with organizations that engage in lobbying or public policy.

“I remember even in middle school, in my social studies class we’d always have every six weeks, we’d write a current events paper about what’s happening in the world right now,” senior Malaika Beg. “Or even US history, we talk about current events and not being able to talk about them, washes you away from reality because you have no idea what’s going on.”

This bill was created in the Texas House and then sent to Greg Abbott to sign. There is also a Senate bill that is similar but goes beyond just history courses and would have similar restrictions on topics in all school courses.

“Honestly, I was surprised that something like this could even get passed, and definitely very frustrated too because you can’t erase history just because you don’t like it,” Beg said. “Teachers can’t talk about how race affects kids in schools, so I just thought this could harm so many kids of color who won’t understand or appreciate their culture.”

Based on a YouGov poll, it was found that 58% of people surveyed strongly disliked the CRT curriculum. The same poll also found that a little over 50% knew what CRT was.

“I am kind of baffled as to how it became such a contentious item in national discussion because I think that most people who feel some kind of way about it or kind of strange about it or fearful don’t fully know what it is and also don’t fully understand what goes on in public schools at the secondary or elementary level,” Shumate said.

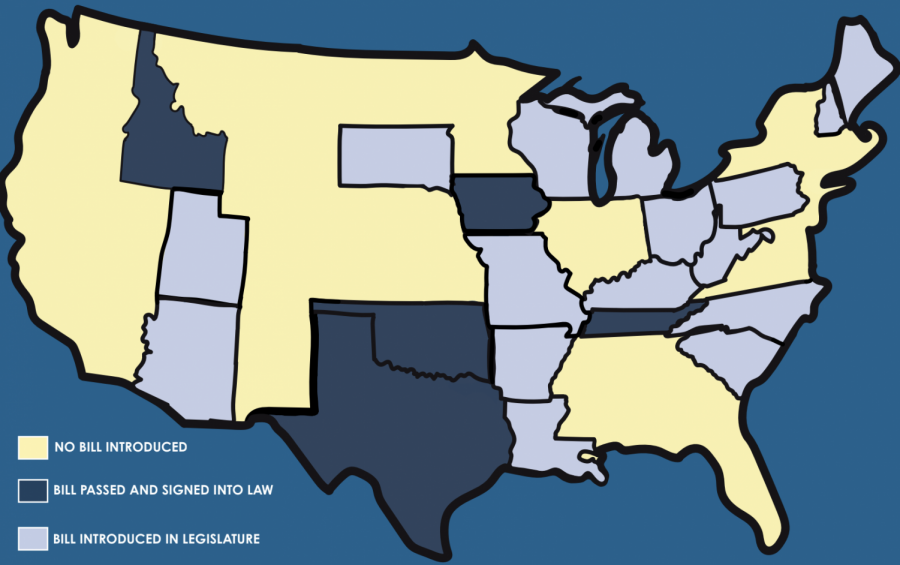

The reality of legislation like this is not limited to just Texas. Five states have already passed a version of the CRT bill into law and it has been proposed in over twenty states and may be passed in more this year.

“I definitely think teachers will react negatively to this,” Beg said. “No matter what their political views are, [CRT is] limiting their freedom of speech, what they can teach to students, and what students need to know about their culture and their history.”

The bill does not specifically lay out how these restrictions will be enforced but allows that responsibility to fall onto school districts and their staff. This responsibility may first go through the school districts on how they will enforce it, but the individual schools themselves will decide how they move forward.

“This feels like a really heavy-handed way to control public education in general and to tie our hands and not allow our students the freedom to think critically,” Shumate said. “Particularly, when issues of race and discussion of police brutality and systemic inequity are in the national conversation on a day to day basis and it’s as though the bill wants to shackle teachers from allowing students to explore their own reality.”

In a poll done by USA Today found that 63% of parents would like for their children to learn about the on-going effects of slavery and racism happening in the United States. On the other side of that, only 49% of parents are in favor of their children being taught about CRT.

“It’s obviously unfair. These are the people who are supposed to be teaching a generation of people, why shouldn’t they be able to tell us what’s happening in our world?” junior Jillian Kelly said. “If they’re supposed to be teaching us how to live in our world, they should be able to tell us what’s happening in it.”

Many courses throughout education are structured around current events and history. This bill limits a lot of what can be taught in those courses and can affect teachers’ lessons and curriculum. Kelly has already seen teachers enact these policies and has seen them steer away from discussing current events out of fear and uncertainty if they are even allowed to.

“Teachers should be able to tell students what’s happening in the outside world, because we’re going to leave high school, we’re going to be thrown into the real world, and if we’re not educated on the events and conflicts that are happening in the real world, we’re going to be confused and unprepared,” Kelly said.