The loud echo of protest music

“The revolution will not be televised. The revolution will be no re-run, brothers. The revolution will be live,” Gil Scott-Heron sings in his iconic anthem of individual activism. The revolution will, indeed, be live, and documented through hard-hitting lyrics and catchy soulful melodies that unite people and incite change.

One uniform characteristic of the most prevalent social and political movements throughout modern history, is their ties with forms of culture and art. One of these forms of art that has had a lasting impact long after movements’ peak, is music.

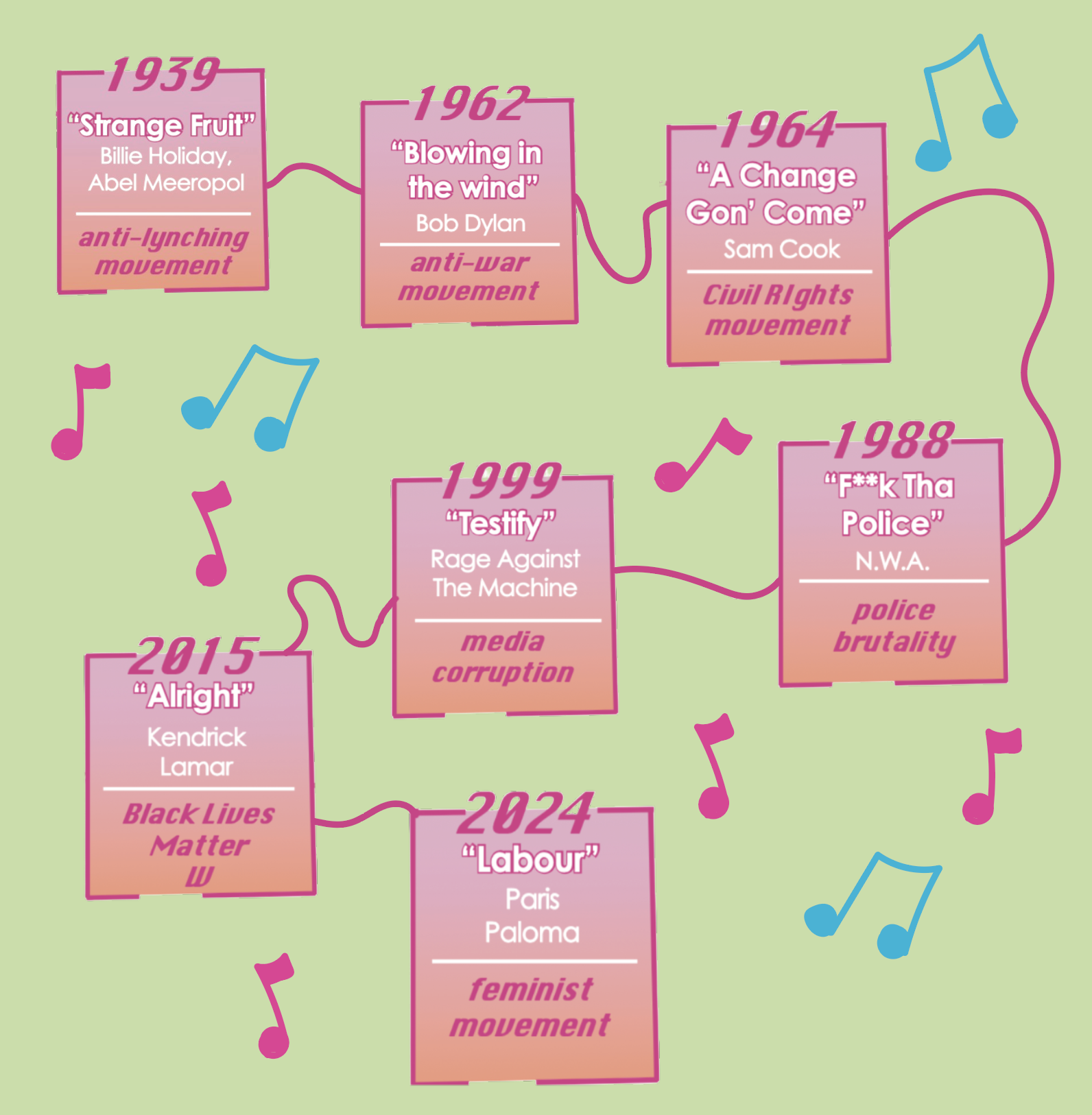

From Joseph Warren’s “Free America” during the revolutionary war in the 1770’s, to Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” which criticized police brutality and emphasized the black American experience in the 2010’s, protest songs have been around since the beginning of America’s modern history. Songs like these have served as a public demonstration of ‘we want change’ for many movements, and a time capsule to the struggles of generations speaking up against injustice.

“Without awareness, people can’t grow, we need awareness for movements to grow” freshman at UTSA and activist Kinda Natsheh said. “Challenging the status quo is very important when it comes to protesting, we need to challenge the systems and cultural norms that are unjust and make sure that there’s attention to issues like racial inequality, environmental degradation, workers rights etc. Music is a very emotional experience and it does have the ability to evoke very powerful feelings, and when people are able to come together to listen to music or perform the music, they feel these emotions as a collective.”

Protest music has been written to express opposition or support for political movements throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. University of Texas Music Theory professor Eric Drott believes the definition of what makes a song a ‘protest song’ is a bit more complicated.

“I think the problem with trying to find a common element with music across the world, is that you end up defining what it is, and then you end up excluding a lot of music that’s used for political action,” Drott said. “Now, I would say that there have been dominant trends, and I think a big one since the 1930s has been with what we tend to recognize as the sort of ‘prototypical’ protest song.”

Drott, who has extensive experience researching music and protest, said that, although there are musical characteristics that are often associated with protest songs, protest music does not conform to any genre and can serve a wide variety of purposes. For example, Natsheh says the song “Olive Branch” by Elyanna motivates her and encourages her to make her voice heard, while Bowie junior Fiona Sobocinski says that the song “Labour” by Paris Paloma was a vocalization of frustration for many feminists.

“Music is different to everybody,” history Teacher Dalton Pool said. “Some people just want to listen to music to escape. Escapism and music can be an important thing. Some people want to listen to music to be inspired. Some people want to expose themselves to new forms of music so they can get exposed to new ideas. I think that’s the great thing about music, is it doesn’t have to take one shape or form, and it can mean so many different things to so many different people, and it can serve so many different purposes.”

‘It’s been a long, a long time coming, but I know a change gon’ come. Oh yes, it will.’ Sam Cook’s iconic solo, “A Change Is Gonna Come,” served as an anthem during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s, describing the struggles of Black America and serving as a verbalization of the hope for a brighter future. The 60’s and 70’s are described by the Denver Center for the Performing Arts as a time dominated by political and social unrest, where the music industry was ‘rife’ with artists fighting to make their voices heard.

“The examples of protest songs that come to mind for me as a history teacher, a lot of them come out of the 60s,” Pool said. “We see a cultural movement that includes art and music, and it’s associated with the counterculture movement, with the anti-war movement of the 1960s and even somewhat with the civil rights movement. So all these different social movements, and a very divided time in U.S. history in the 60s, produce all these different art forms, and people really express their disagreement with the government or with economic policies.”

Both the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement produced over a decade of art and culture that is often used to characterize an incredibly trying time for many Americans. The Library of Congress’ definition suggests that music served to motivate people through long marches, for psychological strength against harassment and brutality, and sometimes to simply pass the time during the Civil Rights Movement.

“During the civil rights movement, music definitely helped foster a sense of collective identity among everybody who was sharing their activism,” Sobocinski said. “When activists gathered together for peaceful protest, like sit-ins or marches, singing songs together reinforced the shared purpose of their struggle for equality. It created an emotional bond and also kind of provided support especially during the moments of fear, anger and frustration.”

Drott mentioned that in other areas of the world, like France, also experienced a rise in music characterized by social or political messages, but what made the United States different was that they were triggered by precipitating events like the Vietnam War and Civil Rights Movement.

“Ultimately, in times of oppression, the protest music or the artists get louder, and they get not more aggressive, but more to the point,” Pool said. “We obviously saw it a lot with Vietnam, lots anti-war music coming out of that time period.”

Though Drott argues that protest music belongs to no specific genre, he notes that there is one exception to this model, and that is hip-hop and rap. An article published by AP News in August of 2023, defines hip-hop as a genre born in “response to social and economic injustice in disregarded neighborhoods.”

“I think that hip-hop and rap are the most powerful genres for political protests,” Natsheh said. “Of course, there’s still songs here and there that are from a different genre that I think are just as influential, but historically hip-hop and rap, especially in the past 40 years, have been great at addressing issues like racial injustice, police brutality, economic inequality. A lot of rappers like Kendrick Lamar, Tupac Shakur, they’ve used their talents as tools for resistance.”

Britannica describes hip-hop as a combination of rhythmic speech, sampling, and deejaying. With the catchy-ness of the dominant drums and powerful rhythms, hip-hop has made its way from its origins in the South Bronx to claiming nearly a quarter of all music streams worldwide in 2023, according to Spotify newsroom.

“Hip-hop is a truly global phenomenon now,” Drott said. “One of the things that’s kind of common about hip-hop globally is that it tends to be a genre that various local minorities will adopt because they sort of see themselves occupying a similar position as African Americans in the United States.”

The genre’s early years were dominated by political commentary and amplification of the black experience, but more modern examples of hip-hop exhibit different characteristics. In an article published by The Michigan Daily in 2023, author Karis Rivers argues that modern hip-hop has moved away from political commentary, and has become commercialized.

“Those who follow Senegalese hip-hop say that there’s almost an expectation that it is political music,” Drott said. “What ends up happening is the sort of musical aspect of the music can often get kind of sidelined, especially when people from the United States are interested in protest in West Africa, and they get into some local hip-hop musician maybe in Senegal or wherever, people don’t think very much of their music, but precisely because there is a sort of expectation that hip-hop is now political in some way. Some music is valued way higher, because it’s sort of doing what we expect, which is a vehicle for protest.”

An important contrast between the protest music of the 60’s and 70’s and more modern examples is the emergence of music streaming platforms. These streaming platforms have made it much easier for people to create, share, and listen to music.

“I think it’s easier to kind of find those people that you really identify with and attach to them today,” Pool said. “I think music is becoming more accessible to people. An artist being able to get content out there easily has kind of compartmentalized music and culture in a bunch of different ways. Each little subject has its own corner, and it’s less mainstream or mono culture. For example, everybody knew who an artist like Bob Dylan was, but an artist that somebody really identifies with today, maybe only 1% of Americans actually knows who they are, but they really identify with that person.”

The access to streaming platforms and social media, where content can be created and shared easily and quickly, has allowed for activists of a variety of causes to be able to unite and bring attention to issues in new ways.

“Due to social media being so big, we’re definitely seeing things blow up in a different way, and we’re seeing more musical variety,” Sobocinski said. “People do listen to a lot of different music, and they don’t just listen to what’s on the radio now, which allows for new, emerging, artists and people with different perspectives to get their music out there.”

In the 60’s and 70’s, a hit song like Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” easily became a nationwide anthem. In the age of music streaming apps, millions of different artists and genres can be accessed at the push of a button, and the songs people coin as anthems for their personal activism have become much more individualized.

“I think music still has a very significant impact today, but It’s role in the way that it influences social movements definitely has evolved,” Natsheh said. “It may not have the same central place as it did in other movements, but it’s definitely still a very powerful tool in shaping activism.”

One of the most obvious examples is the rise of discourse about queer people in music. A rock artist who went by the stage name Jobriath, was considered the first openly gay rock musician signed by a record label only 52 years ago. Now, many of the chart-topping musicians are members of the LGBTQ community, and are vocal about queer rights.

“Originally in the 60s, 70s, 80s, artists couldn’t be as overt about their position, because it was still such a social stigma to identify with that community,” Pool said. “More recently, a lot of the activism and a lot of the music around the LGBTQ issues has been more overt and has been more explicit, just in terms of voicing the artist’s voice, and their opinion, and getting their message out there in a way that is less hidden and more in your face, because it is more socially acceptable.”

The popularity of many songs that serve as examples of protest anthems today can be accredited to their ties to political and social issues that people were passionate about at that time. However, a relationship with a controversial movement sometimes leads a song to face barriers in the industry.

“A classic protest song like Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On,’ he had to struggle to get it produced,” Drott said. “His record label did not want it to be released. They worried he would ruin his career and ruin his image that they’d worked so hard to cultivate. But eventually it managed to come out.”

In 1989, the popular 80’s Hip Hop group, N.W.A., Released a chart-topping rap song, “F**k Tha Police,” which highlighted the prevalent issues of police brutality and racial profiling faced by black Americans. The song was eventually banned from a number of main-stream American radio stations, and eventually from MTV Entertainment in 1989. Several other songs that served as anthems for the movements of their time were also banned or restricted from public radio.

“I think that by continuing to write songs that go against the grain of what we’re being fed in our media, it definitely benefits the greater population,” Sobocinski said. “In Germany during World War 2, they had an entire art museum designated to banned art, to make fun of it, and an entire other one to show off ‘acceptable’ art. Everybody started going to the banned museum because they wanted to see, and novel at, what was being banned. It was ineffective in the end.”

An article published by the University of Wisconsin in February of 2024, details the banning of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” The song, written in protest of Jim Crow Laws, was rejected from several record labels before being published by Commodore Records years later. Regardless of the efforts of those who attempt to suppress or silence protest music, the words of eager activists often end up finding their way into the ears of those who value their message.

“Music does have a unique power to combine emotional, psychological, and social characteristics,” Natsheh said. “I mentioned how music was really important in creating an emotional bond between protesters and that is definitely still prevalent because music is a very emotional experience and it does have the ability to evoke very powerful feelings. When people are able to come together to listen to music or perform the music, they feel these emotions as a collective. It just has its own personality, and I think that’s why people are so attached to it.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of James Bowie High School. Your contribution will help cover our annual website hosting costs. Any contributions made through this service are NOT tax deductible. If you would like to make a tax deductible donation OR to subscribe to our print edition, please contact us at [email protected].