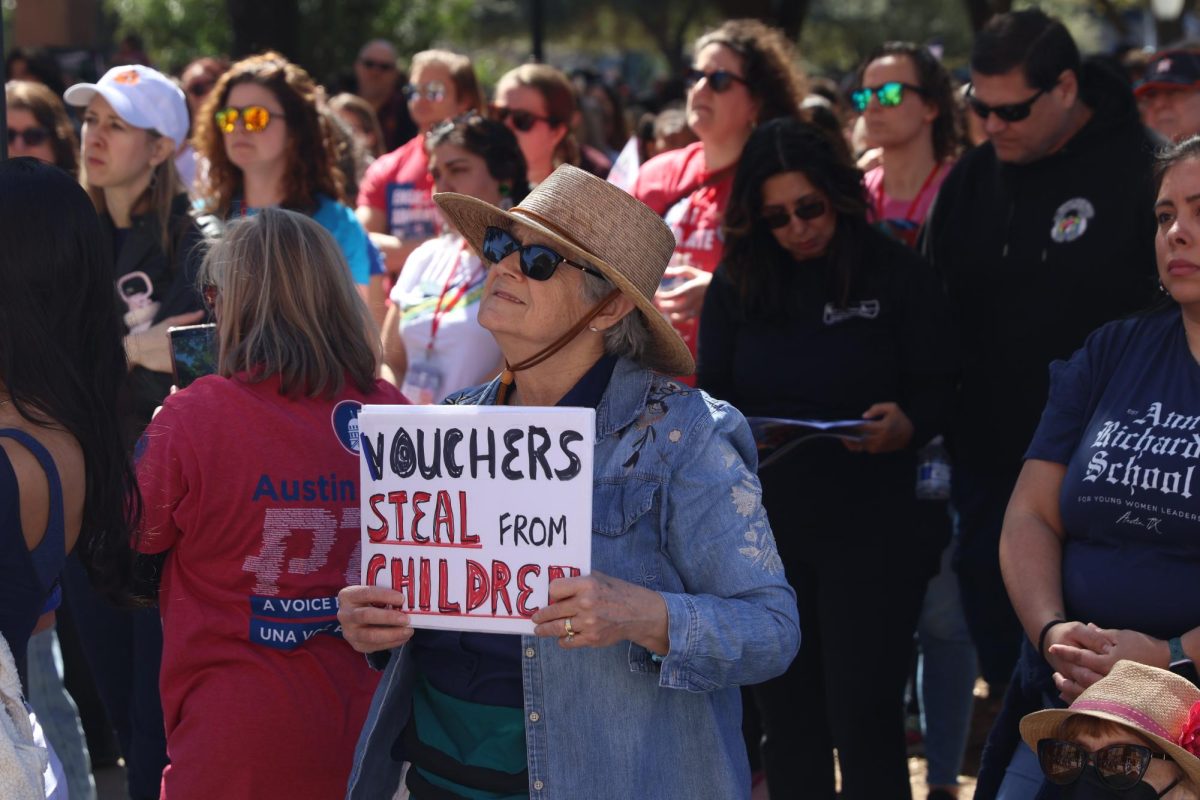

On February 5, 2025, Senate Bill 2 (SB2), which would create an Education Savings Account (ESA) program in Texas, advanced through the Texas senate. Following suit, House Bill 3 (HB3), another ESA program proposal, was filed in the House of Representatives.

ESAs are a voucher-like program which would establish bank accounts, funded from state taxpayer money. This money would go to the families in the voucher program who choose not to educate their K-12 students through public school. Additionally, the bank accounts will be used to pay for educational expenses, such as private school tuition. Currently, two different bills which would establish ESAs are being considered in Texas’s 89th legislative session.

“The state already gives money for public expenses which benefit everyone, which is the point of public education,” junior Annaliese Evans said. “Money going into private education doesn’t benefit everyone, like it should. If that money were to go into public schools it could cover a wider variety of students and their education.”

Currently, representatives supporting vouchers hold the majority in both chambers. 19 of the 31 members of the Senate already voted to advance SB2, and 75 of the 150 House members who signed on as co-sponsors of HB3, plus the bill’s author, would be enough to pass the bill in the House. While the bills from both chambers would establish ESAs, HB3 addresses more than SB2, and there are differences in spending priorities and amounts between the bills. Further, both bills are currently in the House’s Public Education Committee, leaving potential for continuous changes and amendments.

“If it comes out of the committee, where we can make changes, then it goes to the floor, and on the floor we can do floor amendments,” Rep. James Talarico said. “Our two options to combat the bill are either to make amendments or vote it down.”

While both bills propose using $1 billion per year to fund ESAs, under SB2, ESAs would have a per-student allotment of $10,000, whereas under HB3, the per-student allotment would be 85% of what public schools get through state and federal funding, with the minimum allotment being $10,000. State budget analysis of HB3 projected the costs of the program rising from $1 billion to almost $5 billion per year by 2030.

“The budget of the program increases over time because the voucher becomes an entitlement and it has to create slots in the coming year,” Rep. Sarah Eckhardt said. “The students who are in the program will be holding down that voucher however long they are in K-12, and then there will be others coming in behind them, so it has a compounding effect.”

Neither bill contains an income cap for families participating in the program. Under SB2, when demand for ESAs exceeds funding, students whose household income falls below 500% of the federal poverty level, which is $156,000 or less for a four person household, would be prioritized. Under HB3, students would be categorized into four tiers of priority. The highest priority tier would be disabled students at or below 500% of the federal poverty level, then students at or below 200% of the federal poverty level, then students between 200% and 500% of the federal poverty level, and finally students above 500% of the federal poverty level.

“High income families already have the money and means to go to private school, and not everyone can do that,” Evans said. “Even if regular families got a voucher, they still may not be able to afford private school.”

Under SB3, students with disabilities would receive $1,500 on top of the baseline $10,000 allotment. Under HB3, students would receive the allotment amount plus an additional amount calculated based on what the state spends on special education per student in public schools, potentially up to $30,000 total per year. Additionally, under HB3, private school parents would be able to request that a public school evaluate their student for a disability, which is already mandated in some cases under federal law, and the public school would have to evaluate that student within 45 days.

“Under the voucher program, while you may get a larger voucher if your child has some kind of disability, it’s nowhere comparable to what public education must provide to a student with disabilities,” Eckhardt said. “Up to one third of students in public education have some level of disability.”

Under both bills, private schools would not have to fulfill any additional requirements to participate in the program. Private schools participating in the program would still be able to reject students, not provide learning accommodations or evaluations, and not administer standardized tests or publish testing results.

“I would like the legislature to reject the vouchers and increase the funding for public schools, that way we can get a better education,” Evans said.