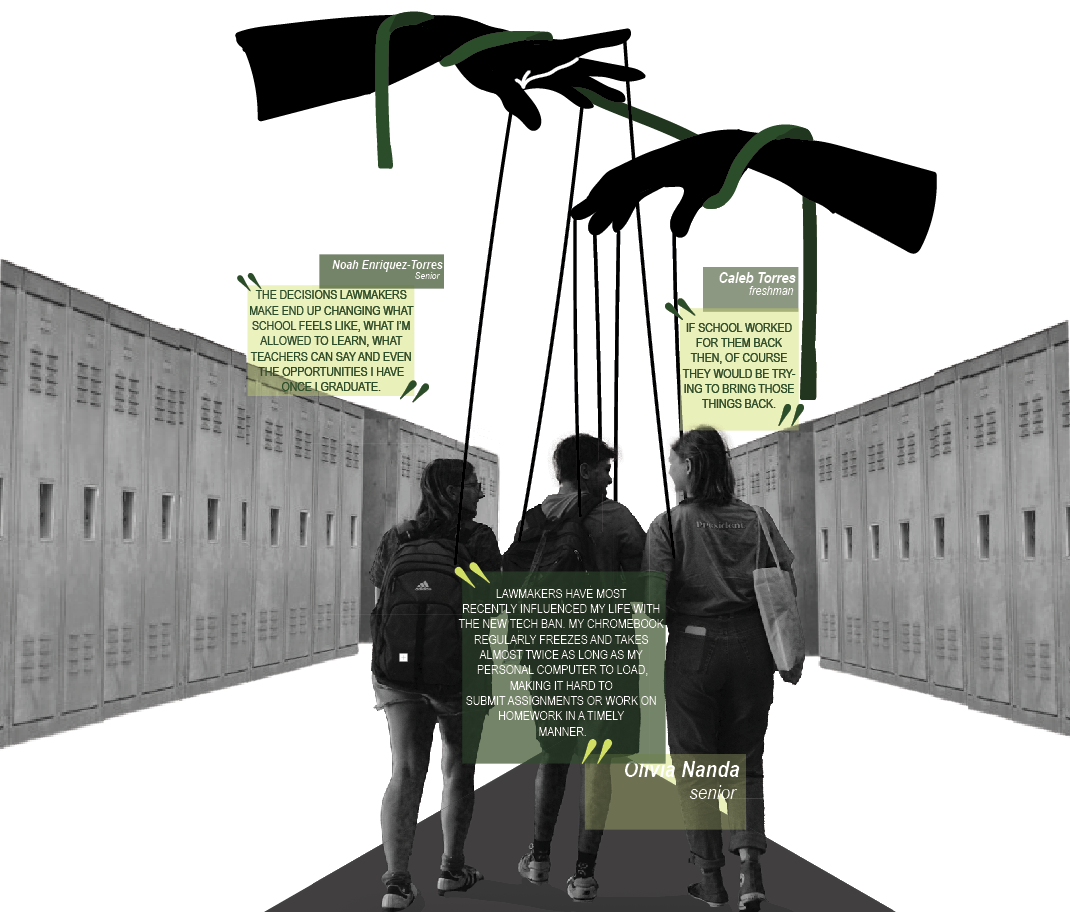

Hearing about a new proposed law, junior Avery McMahon was shocked. As co-president of the Bowie book club, she was disgusted. Reading further, she couldn’t help but think: school libraries are under attack.

Researching the proposal further, she found that House Bill 900 (HB900) allowed books to be removed from schools based on what, she believed, were the personal opinions of Texas Republican politicians.

She had questions: What kind of government dictated what an individual could read on their own time? How did HB900 even get passed, when legislators know that it puts students’ futures at risk?

“Books are powerful, because they teach us about the world and our place in it,” McMahon said. “How are we supposed to have these discussions if we can’t read challenging literature? If the state can get away with this legislation, then they might go after the Austin Public Library, then start attacking private book vendors. Eventually, some of our books will be outlawed, and we’re not going to be able to read them because the state arbitrarily believes they’re inappropriate.”

THE BOOK BAN

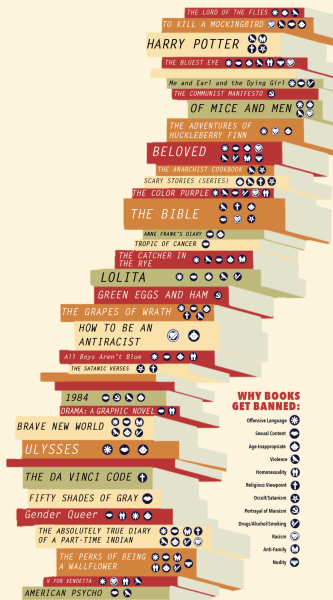

HB900 was scheduled to take effect September 1, alongside over 770 new laws passed by the Texas Legislature. This law requires booksellers to rate all books based on their depictions of sexually explicit topics. Booksellers believe this law, also known as the Restricting Explicit and Adult-Designated Educational Resources (READER) Act, truly aims to unconstitutionally regulate free speech, which is protected under the 1st and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

“This bill absolutely restricts free speech, because the whole point of reading a book is to learn information and to tell a story,” senior literature club vice president Katherine Kuster said. “Not allowing people to read the books they want in school is stifling self-expression. It’s another try by Republican lawmakers to stop information spreading around.”

According to Bowie librarian Tara Walker-Leon, the required ratings are based on vague standards; the law’s broad definitions leave too much room for personal opinion. If the Texas Education Administration (TEA) disagrees with a bookseller’s rating, it can overrule their decision without explanation. Senior Grace Steffenson believes this gives the government absolute authority to decide what books are allowed in schools.

“Any law that restricts literature, or any type of free speech, is never in anybody’s self-interest,” Steffenson said. “It’s not for children’s benefit, the laws are only used to push an agenda. The real purpose is to manipulate, to benefit a (political) party and its members.”

Under the law, books that are rated “sexually explicit,” meaning they contain content considered “patently offensive” by unspecified community standards, are banned from the shelves of public school libraries. Books that are rated “sexually relevant,” meaning they have any representation of sexuality, can remain in school libraries, but can only be read by a student outside of school, with written parental consent.

“I think this is hilarious,” Walker-Leon said. “You tell kids not to read a book, and now that’s exactly what they want to read. We challenge orders like this, it’s human nature.”

As a member of the Bowie Literature Club, Steffenson believes that banning classic works would restrict important learning that students wouldn’t find anywhere else. The broad definitions of HB900 could result in banning these works, such as Romeo and Juliet, Of Mice and Men, Anne Frank’s Diary, The Great Gatsby, To Kill A Mockingbird, and many more respected works. Even the Bible could be at risk under the bill’s definitions.

“There’s a reason that classic works are classic,” Kuster said. “They were typically written in politically tense times, and they offer important political and social commentary. Making it difficult for students to read these books stops that information from being spread around, so students don’t realize that they can stand up for what they believe in and that you can speak out against what you think is wrong.”

The bill grew out of a 2021 inquiry by former state Representative Matt Krause, who asked Texas school districts if their libraries contained any of 850 books that he considered offensive, primarily related to race and sexuality. This list inspired Representative Jared Patterson to remove about three dozen books, which he identified as personally offensive, from his own school district.

“When that list came out, I had my library aides go through the whole thing,” Walker-Leon said. “We looked for commonalities in the books, and we noticed they are all books that question racism, LGBTQ awareness, or abortion. So it’s clear that HB900 will extend to attack those groups, too.”

Patterson is now the primary author of HB900. McMahon believes the bill removes local control over school libraries in favor of a “statewide regulatory regime.” Instead of leaving decisions to parental and community input, the state has seemingly seized local libraries, opponents say.

“This bill makes reading feel bad,” McMahon said. “Instead of showing you all the books you can read, and telling you to find one you like, the government is saying: ‘Here’s all the books– but we’re going to tell you what you can read.’ Everyone prefers reading the things they want to read, versus being assigned a book by the government.”

CENSORSHIP?

Since the law was introduced, BookPeople CEO Charley Rejsek has been protesting it. BookPeople is the largest independent bookstore in Texas, and has been an Austin staple since its doors opened in 1970. Blue Willow Bookshop has a similar reputation in Houston; these two bookstores, aided by a team of literary defense organizations, have filed a lawsuit in hopes of blocking HB900.

“I’m glad they sued because this bill was another one of those restrictive laws that relies too much on personal interpretation,” Steffenson said. “It’s the same concept as the Critical Race Theory argument, people don’t even know what it actually means, but they’re against it anyways. They just hear these keywords and go crazy about it, but nobody actually knows what these bills are doing, and what they can potentially take away from us.”

The plaintiffs believe HB900 violates the 1st and 14th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution. According to the complaint filed July 25, this law “is an over-broad and vague content-based law,” which “targets protected speech” and is not “narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest.”

“Setting aside the fact that this law is clearly unconstitutional, booksellers do not see a clear path forward to rating the content of the thousands of titles sold to schools,” Rejsek said. “Booksellers should not be put in the position of broadly determining what best serves all Texan communities. Each community is individual and has different needs. Setting local guidelines is not the government’s job either; it is the local librarian’s and teacher’s job, in conjunction with the community they serve.”

According to the plaintiffs, the “Book Ban” compels library vendors to express the government’s views, even if they don’t agree with those sentiments. This can be interpreted as prior restraint, which is a form of censorship that allows the government to review written content and prevent its publication.

“The Book Ban harkens back to dark days in our nation’s history when the government served as licensors and dictated the public dissemination of information,” the plaintiff group said, in the public complaint issued against the bill. “The lessons from our history should be learned, not ignored, and the constitutional prohibitions against censorship regimes should be respected, not rebuffed.”

Alongside the ethical concerns, book vendors are shocked to hear that the state will be providing no funding for the completion of this task; they are given more work, and no money to do that work.

“There are so many logistical nightmares here I don’t even know where to start,” Walker-Leon said. “Nobody wants to rate these books, it’s a game of censorship hot potato. It’s a mess, and I think it’s illegal. They are going to put book vendors out of business and run school libraries to the ground.”

The Texas House passed the bill 95-52, with 12 Democrats in support. The Senate voted 19-12, zero Democrats in support. Governor Greg Abbott signed the Book Ban on June 13. It was scheduled to take effect on September 1, and applies to the 2023-2024 school year. Katy ISD was the first to cease all library book purchases after the bill’s passage. Dripping Springs ISD now requires parental permission for all books categorized “YA.” Some of these books are considered literary classics, like Fahrenheit 451 and Lord of the Flies.

“If students are confused about something that happens in a book, they should be able to explore, and to question, and to have conversations about the things they saw or read, that opportunity shouldn’t be locked away from them,” McMahon said. “We’re not really kids, we’re teenagers about to be adults. Shielding us from the real world is not going to help us, at all. It’s only going to hurt us in the future.”

SILENCING STUDENT READERS

The moment she heard about HB900, Walker-Leon knew something was wrong. This bill could have major implications on the school library that so many of her students rely on, the library that she has dedicated much of her life to. She runs the library by herself, and spends all of her time ordering books, organizing shelves, and ensuring things run smoothly in Bowie’s literary home.

“The Bowie library is a place for all students here on campus, no matter if they’re a big reader or not,” Walker-Leon said. “This is a community space, and we work to make sure everyone feels included here.”

First reading about the bill, she was optimistic that it wouldn’t pass. After all, she believed it was an obvious infringement of Americans’ 1st Amendment rights. Attending the Texas Library Association conference last April, though, she began to lose hope.

“I got a chance to talk to fellow librarians, colleagues, and vendors, and everyone was freaking out,” Walker-Leon said. “I realized that it was actually very serious, and it was probably going to pass.”

The Bowie library stocks its shelves with books from multiple different vendors, such as Follett, MackinVIA, and BookPeople; with the unclear standards established in the bill, how are these different companies all going to get on the same page when rating these books?

“I don’t think publishers can all agree to one rating,” McMahon said. “It’s hard for that to happen, when everyone who reads the book will have a different experience with it, and a different idea of what the book’s about based on their own understanding of it. They’ll take a long, long time to agree on one rating.”

Both Kuster and Walker-Leon believe HB900 targets student readers and school librarians. As publishers fight the state over the rating system, school libraries will become emptier and emptier while orders for books become delayed.

“Texas is just creating more obstacles than necessary to steal books from the hands of kids,” Walker-Leon said. “It’s another one of the state’s attacks on public education.”

So why would Texas choose to create a bill like this? Why would legislators take library control from the community, and reserve it for the state? Walker-Leon believes the blame lies on the parents.

“Parents are probably freaking out because they can’t control what their kids have access to,” Walker-Leon said. “Their kids have their phones in their hands, they have access to all different kinds of inappropriate materials on the internet. Parents can’t control that; but they can control the books in their schools.”

She believes parents are using their frustration to control libraries and public schools. She recognizes this movement as another attack on public schools, which she believes contributes to a larger, systematic attack, which aims to privatize education in Texas.

“The way the privatization movement contributes to this problem, just makes me aggravated with the whole thing,” Walker-Leon said. “I’ve been a teacher for 20-something years, and I used to think I was being paranoid, believing that they’re trying to destroy public education. Now, though, I’m certain they are.”

RETURNING BOOKS TO THEIR SHELVES

District Judge Alan D. Albright, who presided over the lawsuit filed by BookPeople and their team, has granted a temporary injunction, meaning the state cannot enforce the law. The fight isn’t over though, as the lawsuit is ongoing. McMahon believes students still need to protest and make their voices known.

“When students have something that frustrates them enough, they’re very good about inspiring change,” McMahon said. “Even if you don’t read that much, and think this doesn’t affect you, you need to care about this. If your friend reads, your brother reads, your sister reads, your friends read, if you know anyone who reads, they should be able to pick what it is they’re reading.”

What makes this bill unfair? Literary advocates believe that the books often singled out by politicians, like Representatives Krause and Patterson, are those that explore sexuality and race; advocates claim these topics have been caught in the crossfire of culture-war politics, but remain important for teens as they grow into the individuals they’re becoming.

“Texas lawmakers are historically Republican, and they’re very radical,” Kuster said. “These bills are trying to ban books and stop people from expressing themselves. None of this is in kids’ self-interest, and it doesn’t actually help anybody. You could even hit it from an economic standpoint. This could ruin the economy because thousands of books will stop being sold to schools. They’re just messing up everything.”

Walker-Leon believes this is a problem that students need to pay attention to; according to her beliefs, when the state starts attacking public institutions, they are taking a dangerous turn into fascist territory. McMahon fears that state control over school libraries is censorship in its rawest shape: censorship which starts at the school level and expands to control the state, and soon might sweep the entire nation.

“In history, when they start taking libraries, they start to control and suppress our voice,” Walker-Leon said. “When any government wants to control knowledge, control information, and suppress different groups of people, it’s incredibly problematic. It’s under the guise of protecting our children, but really they want to use this legislation to control our children.”

McMahon encourages students to protest this change. She believes one of the greatest ways to effect change is to get directly in contact with Texas’ legislators: to her, petitioning and sending letters are the best ways to protest. Walker-Leon wants students to know the method to protect the people from targeted legislation such as this: stay aware.

“So many people are so busy, I get it, but they’re not paying attention,” Walker-Leon said. “It’s important to be aware, to stay informed. Follow educational outlets on social media, make it your business to educate people. Then, vote accordingly. Voting is a weapon, so we need to make sure to vote for politicians who support us and the public libraries our state is attacking.”