Maturity and behavior broken by social isolation

Vandalism and tagging have been common around campus this year, especially in bathrooms. Custodians and administrators have been diligent about removing the damage, but some have cost the school much-needed money.

December 15, 2021

Brijette Galvan peered around nervously.

It was the first day of high school, and her first day being back in person for school in almost two years.

Tall buildings, chaotic directions, countless hallways, and with only a little yellow piece of paper to guide her, she began to sweat and panic.

“What class do I go to first?”

“What is a block schedule, and why do I only have four periods today?”

“How much homework will I have?”

As the questions piled on, Galvan reflected on the hardships of coming into high school as a freshman, especially coming off of the lengthy COVID-19 quarantine and remote learning, and trying to adapt to new high school procedures when her last full year of school was sixth grade.

“Personally, adjusting to in person school was a little hard for me and my friends,” Galvan said. “Since it is our first year in high school, we don’t know our way around the school or know as much about the school as others, which made me nervous that I wouldn’t get the hang of being in high school, especially after quarantine.”

After being in isolation for 18 months, underclassmen have entered high school without previously being in an in-person classroom since middle school, and for freshmen, their last full year of school was in sixth grade, when they were just 11 or 12 years old.

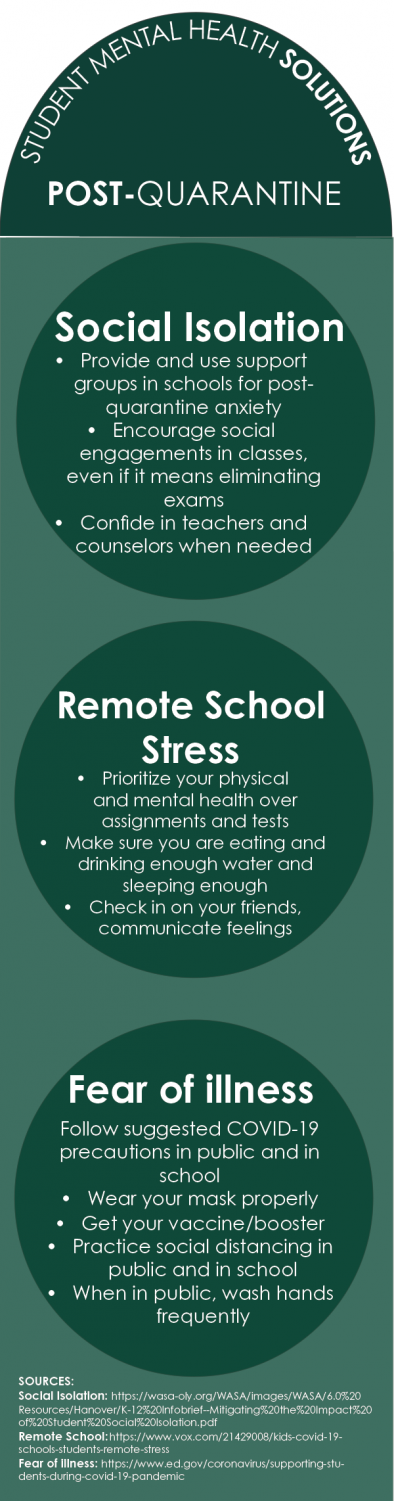

According to an article from the Harvard Crimson by Yuen Chow and Natalie Kahn, 63% of freshmen reported that COVID-19 resulted in a decline in their mental health.

“91 and 67% of this subset cited social isolation and stress, respectively, as additional causes,” Chow and Kahn said in the article. “Additionally, 16% of respondents pointed to income insecurity from the pandemic as a factor that worsened their mental health.”

Due to this abrupt shift from isolation to in-person, many examples of bad behavior and acting out have arisen from underclassmen. Just at Bowie, students have set a fire in the bathroom, written on walls, attempted to flip tables, poured milkshakes on other students’ heads from the second floor of the academic building, thrown food at each other and at walls, and more.

“With only being at Bowie for almost one semester, there are some things that have been happening that are out of the ordinary,” Galvan said. “For example, vandalism, especially in the bathroom; there is almost always a lock in a stall that is broken, or a soap dispenser that is missing, and there are always some drawings on the sides of the bathroom stalls.”

As administrators have investigated, it has been discovered that most, if not all, of the acting out has been initiated by underclassmen, those who haven’t been in high school before the pandemic broke out.

“Although I am shocked about the severity of the misbehavior, I also think it’s expected because they have been isolated for 18 months,” senior class president Vanessa Nguyen said. “With lack of social interactions, teachers’ rules, and school expectations often provided at school can lead to acting out, which is the situation we’re seeing at Bowie currently.”

Since the pandemic caused a decline of learning for students globally, their maturity and development have ultimately been stunted, according to an article by Emily Henderson from News Medical Life Sciences. In the article, she notes that 80% of parents believe that their children are learning less from digital system and that their levels of understanding are sinking.

“COVID-19 and online school have hindered a lot of our social interactions, which has caused problems in the underclassmen’s behavior and their development in the last years of middle school, which are crucial to their success in high school,” Nguyen said. “Being in school tends to keep your maturity level in check, so it’s hard for them to adjust when they haven’t had any of those experiences; I assume that for teachers, it’s been hard to teach when the class’s maturity level isn’t where it’s supposed to be.”

According to Academic Dean Kaylin Brett, the behavioral misconduct at school is a representation of an “unfinished learning” concept, creating an environment for these underclassmen where they feel as if because of COVID-19 isolation, they will never catch up, will continue to fall behind in classes, and therefore act out.

“If I had to put it in a nutshell, it’s the fact that kids went from having total power to now having to be structured, and that it feels like they’re being micromanaged,” Brett said. “Not having that control anymore is what’s causing the retaliation we’re seeing this year.”

On top of coming back to in-person school, many grading policies and strategies have been implemented, especially non-senior core courses. This is another factor that has contributed to the frustration of grades from underclassmen that led to their actions. Freshman Isabella Verette has had first-hand experience with these actions this year.

“My friends and I in Algebra 1 hate the new grading policy,” Verette said. “Me personally, I’m not a good test taker and only giving me five questions for 75% of my grade when I might be succeeding in classwork and homework makes taking the tests even more stressful.”

Moving forward, Brett believes it’s crucial for students to continue playing catch-up throughout the year inside and outside of classes, with homework, and joining clubs, with the help of upperclassmen student leaders to aid them in adjustment to high school following the 18 months of quarantine that took early high school away from them.

“Administration relies on student leaders to help underclassmen get involved in school,” Brett said. “With the help of seniors, they can set the example for future kids, while finding their place by getting involved in activities.”