Gentrified

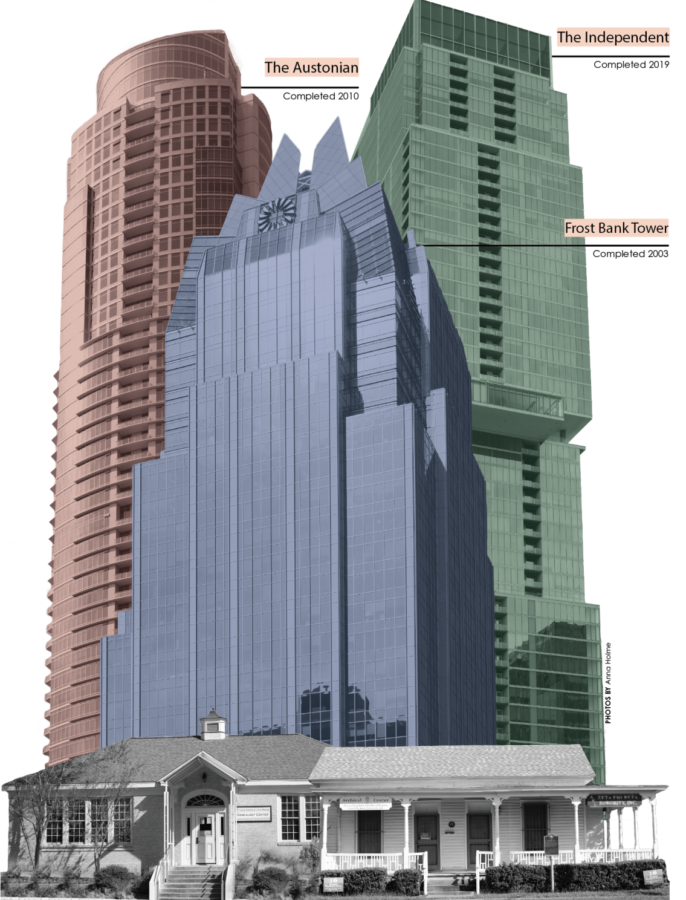

Three buildings constructed this century dominate the Austin skyline, overshadowing homes on the East side that have been around since the 1950’s. Many long time Eastside residents are being pushed out of their homes for new developments.

December 14, 2021

Austin housing prices skyrocket as pre-existing communities are being pushed out

She has six brothers and two sisters. A father who works below minimum wage. She was told she would have to move out because her landlord just sold their house. Under such short notice, their new house is three to four times smaller and significantly more expensive. This scenario describes the teenage experience of Susana Almanza, an East Austinite who has been a resident in the city her whole life, for over 69 years.

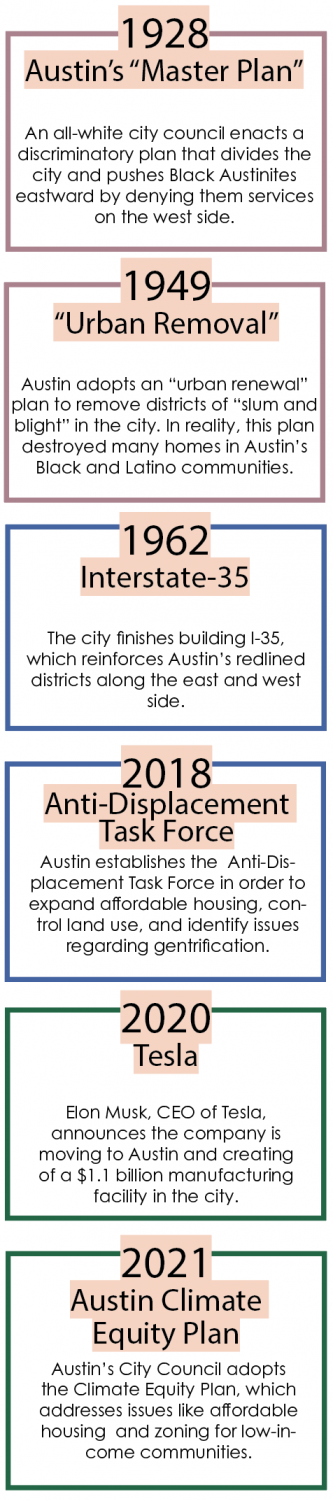

With Austin’s recent population boom, housing prices have skyrocketed. According to Norada Real Estate Investments, From 2010 to 2019, Austin’s median home price increased from $193,520 to $318,000. Some estimates, as reported by KUT, have even estimated that within the past year, rent prices in Austin have risen 20%, even though the rent increase per year normally is around 5%.

With the cost of living climbing higher and higher, many families are struggling to keep up and are being pushed further out of Austin’s urban core. This phenomenon reflects what is known as gentrification.

“Gentrification, in Austin, is the displacement of indigenous peoples in East Austin who were forced to move,” Almanza said. “Gentrification has been displacing low-income and communities of color from their traditional home base and gentrifying that area. Most of the houses that were built and bought in East Austin were bought and built for $2,000 to $8,000. Those homes are now worth $350,000.”

Almanza saw early on in her youth the way her community was being affected by gentrification, such as her family being pushed out of their home when she was a teenager. She decided she wanted to take action, so she co-founded the organization PODER (People Organized in Defense of Earth and her Resources). PODER consists of a group of Chicano and Chicana activists and community leaders in East Austin. One of PODER’s focuses has been East Austin’s gentrification issue.

“We’ve seen a lot of a small mom and pop businesses go under, and we see new restaurants that are more expensive, that cater more to the upper-middle-class income earners,” Almanza said. “So we have seen major devastation.”

Austin zip code 78721, located in East Austin, was ranked the fourth most gentrified zip code in the entirety of the United States by realtor.com, with a five-year median sale price increase of 148.2%. The drastic soar in housing prices and property taxes has forced many East Austin residents to move to the outskirts of the region, like Pflugerville, Manor, or other parts of North Austin, where the cost of living is cheaper.

“I’ve seen the local businesses that I love so much not be able to afford rent in the area,” senior Cristina Canepa said. “I’ll come back and they’ll be replaced and a Starbucks will be where the little taco shop that I loved used to be. That’s kind of a small way where I’ve seen corporations come in and be able to buy out smaller businesses in order to renew the area, but it takes away from the personality of the Austin area.”

While gentrification has accelerated in recent years, this problem is not new. Austin has had a long history of segregation that pushed lower-income, communities of color to the east side. And now that Austin has expanded, these communities are being forced out.

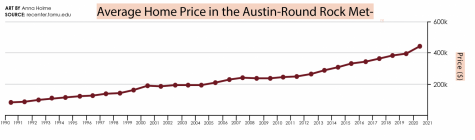

“If you looked at the city of Austin’s ‘Master Plan’ in 1928, that was the plan that would start to relocate African and Mexican Americans to East Austin, and that would become sort of like the modern reservation of where people of color would live,” Almanza said.

Austin’s Master Plan was adopted by an all-white, all-male city council. The plan worked to strategically move communities of color to East Austin by way of denying them necessary resources and services unless they moved eastward.

“It is our recommendation that the nearest approach to the solution of the race segregation problem will [be] the recommendation of this district as a n*gro district; and that all facilities and conveniences be provided the n*groes in this district, as an incentive to draw the n*gro population to this area,” the Master Plan, written in 1928 by consultants Koch and Fowler, stated.

The Master Plan wasn’t the only discriminatory policy endorsed by the city, however. Communities of color were consistently denied the ability to purchase homes or gain loans to buy property on the west side of Austin, a process called redlining. Austin was redlined along the east side so that communities of color were only allowed to buy property there.

“Redlining created a segregated city,” Canepa said. “People of Black or Hispanic background were forced into East Austin, and then white people on the west side of I-35. Redlining really did create two separate Austins. It still continues to affect us because generationally, people have stayed in those areas and wealth has stayed in those areas. So it’s created socio-economic and racial disparity disparities within the city.”

Countless efforts were made to reinforce these redlined districts, such as the construction of Interstate-35 in the early 1960s. I-35 acts as a physical barrier separating the east and west sides of Austin.

“Definitely just looking at the change on the east side is just the absolute biggest part of gentrification in Austin,” Students Organized for Anti-Racism (SOAR) sponsor and yearbook teacher Lindsey Shirack said. “Austin was fully segregated, and placing I-35 where it was and how they developed and assigned neighborhoods was very much done with segregation in mind.”

Austin has had a plethora of other policies put in place to force communities of color and lower-income communities eastward. Austin’s “Urban Renewal” (now called “Urban Removal”) project in the 1960s aimed to renovate neighborhoods of “slum and blight” by eradicating historical homes in East Austin.

“The city came back and said, ‘this area is a slum and blight area, and we’re going to redevelop this area,’” Almanza said. “They used eminent domain, they forced the people to move out and took their land, and then told them ‘your land is only worth this much’ when in essence, it was worth 100 more times and what they were compensated for.”

The historical East Austin community is now experiencing hardships as their land has become more valuable. Large corporations are buying out land and raising the property taxes in the area. Many lower-income families, disproportionately represented by Black and Latino communities, are struggling to keep up.

“East Austin now instead of being considered the ‘bad side of town,’ has become like the ‘cool, hip side’ where you want to create a little startup company or you want to go for brunch and other stuff,” Canepa said. “So I’ve seen gentrification with the new money coming into the area. They see the cheap land as a chance to open up a business for less money. And it’s caused the demographics in the area to change.”

One of the major corporations that has recently moved to Austin is Tesla. In 2020, CEO Elon Musk announced the company’s relocation from California, and on December 1, officially named Austin its headquarters. Other technology companies like Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, AMD, NXP, and Oracle all have locations in Austin. These tech companies have some dramatic effects on the housing market in the area.

“It has driven the cost of living up in Austin by having these tech companies come in,” Shirack said. “To [these companies], it’s an incredible deal. I have a friend who just moved and sold her house for half a million dollars. And that was double what she had paid for it five years ago. And it was bought by someone from California who was basically buying an investment property. She got 10 offers, all over the asking price. That’s how crazy the market is.”

These corporations have brought in a plethora of new jobs, with many of these positions being filled by employees moving in from out-of-state. According to Texas Realtor’s 2021 Texas Relocation Report, Texas gained over 500,000 new residents in 2019.

“I think tech coming in is a good thing and a bad thing,” senior Malaika Beg said. “It’s a good thing that more people can get jobs through these tech companies, but the bad thing is that people are coming in and taking away those jobs from Austinites that have been living here.”

Jobs aren’t the only concern associated with big tech’s arrival in Austin. Tesla’s new headquarters is located in East Austin. This means that the land surrounding the Tesla area is now in high demand from workers who want to live close to their headquarters. This has problematic implications for the people already living in the neighborhood.

“We’re already under siege because of Tesla,” Almanza said. “Montopolis (an East Austin neighborhood) is only about eight to 10 minutes from Tesla. Montopolis has one of the highest amounts of poverty, the median income for the residents is I believe is $33,000 a year for a family of four. So that really shows you that this is a poor, working-class community. We’re now having half a million dollar homes built in a poor community because we’re only eight to 10 minutes away from Tesla. So there’s another side to this big corporation coming because nothing is being put in place to stop the displacement.”

In response to the gentrification in East Austin, in 2018, Almanza and her colleagues Fred McGhee and Jane Rivera introduced the People’s Plan to the City Council, a plan describing six resolutions to combat displacement in Austin. The plan includes concepts like establishing low-income housing and creating a community land trust.

“The city owns a lot of properties, and when I talk about the city, that’s us as public taxpayers,” Almanza said. “The city owns thousands of properties where it can actually be building low-income housing. The city has the ability to really build low-income housing, whether it has partnerships with non-profits, realtors, or other organizations.”

There have been many other efforts to research and plan how to prevent gentrification. The city of Austin created the Anti-Displacement Task Force in 2018. In 2017, the Mayor’s Taskforce on Institutional Racism and Systemic Inequities was created, with a successor organization called the Central Texas Collective for Racial Equity being created in 2020. The UT Uprooted Project was created to research gentrification and inform policy. While the efforts to prevent gentrification are extensive, Almanza argues that there isn’t enough tangible action being taken.

“It’s not that the city doesn’t know about these recommendations, it is that it hasn’t bothered to implement these recommendations,” Almanza said. “Because [the city] doesn’t really care about the poor or communities of color. And that’s a great, great injustice. We need to think about everybody, but specifically, we have to think about the most vulnerable populations and the city really isn’t doing that. [The city] is looking at the middle class, upper-middle-class, and the rich, so this is totally an ‘out of sight out of mind’ when it comes to the working-class people.”

The largest piece of legislation in regards to gentrification that has been adopted by the City Council is the Austin Climate Equity Plan. The plan lays out goals for affordable housing as well, aiming to “preserve and produce 135,000 housing units, including 60,000 affordable housing units” by 2030.

“I know that the climate plan Austin has adopted is a pretty large step for affordable housing,” Canepa said. “But we need to hold the city accountable and make sure they follow through on their promises and actually execute their goals in an effective and timely manner.”

If gentrification trends continue, downtown Austin will become increasingly less diverse. In UT professor Dr. Eric Tang’s study called “Those Who Left,” From 2000 to 2010, Austin’s Black population decreased by 5.4%. Additionally, when surveying Black ex-Austinites who had moved out of the city, 56% of respondents cited “unaffordable housing’’ as their primary reason for leaving, and 63% of respondents lived in East Austin before moving.

“I feel like, overall, kind of, we’re losing the stuff that makes us special,” Beg said. “What makes Austin such a unique city, we’re losing that because we have so many people moving in. People who are a lot richer, who have more money, are moving in and taking out people who’ve been living here for a long time.”

Austin is only becoming a larger and larger city, with a 21% growth rate in the last decade according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Many believe gentrification is bound to become a larger issue as the demand for housing grows in Austin.

“Without any sort of an intervention, I think we’re going to continue to see a lot of what we’re currently seeing, which is, those areas that had previously been neglected will continue to become areas that only higher-income people can live in, which will continue to force families out onto the edges and make it so that people are living even further away from where they work,” Shirack said. “It doesn’t feel sustainable to me, something’s got to give.”

Gentrification is an issue that reveals itself over time. Almanza argues that younger generations have a mindset that will be beneficial to combating gentrification and gives advice for young activists who want to get involved.

“I feel it is the young people, and this young generation, that has more of an understanding that diversity is something to embrace,” Almanza said. “I think that younger generations just need to stay on the path of justice. There is an old indigenous saying that goes like this: there was a time when we were all sisters and brothers, the night sky our ceiling, the Earth our mother, the sun our father, our parents our leaders, and justice their guide. If we continue to follow that concept of justice being our guide, by looking at fairness and equity, we will become a better society.”