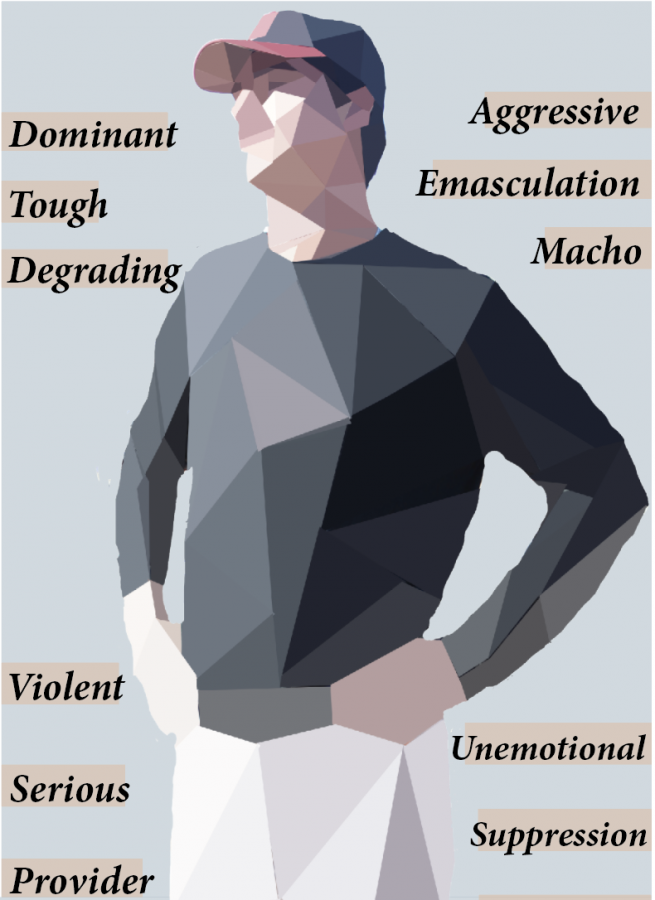

Toxic Masculinity

Words given by students when asked what comes to mind when hearing “Toxic Masculinity”.

January 8, 2020

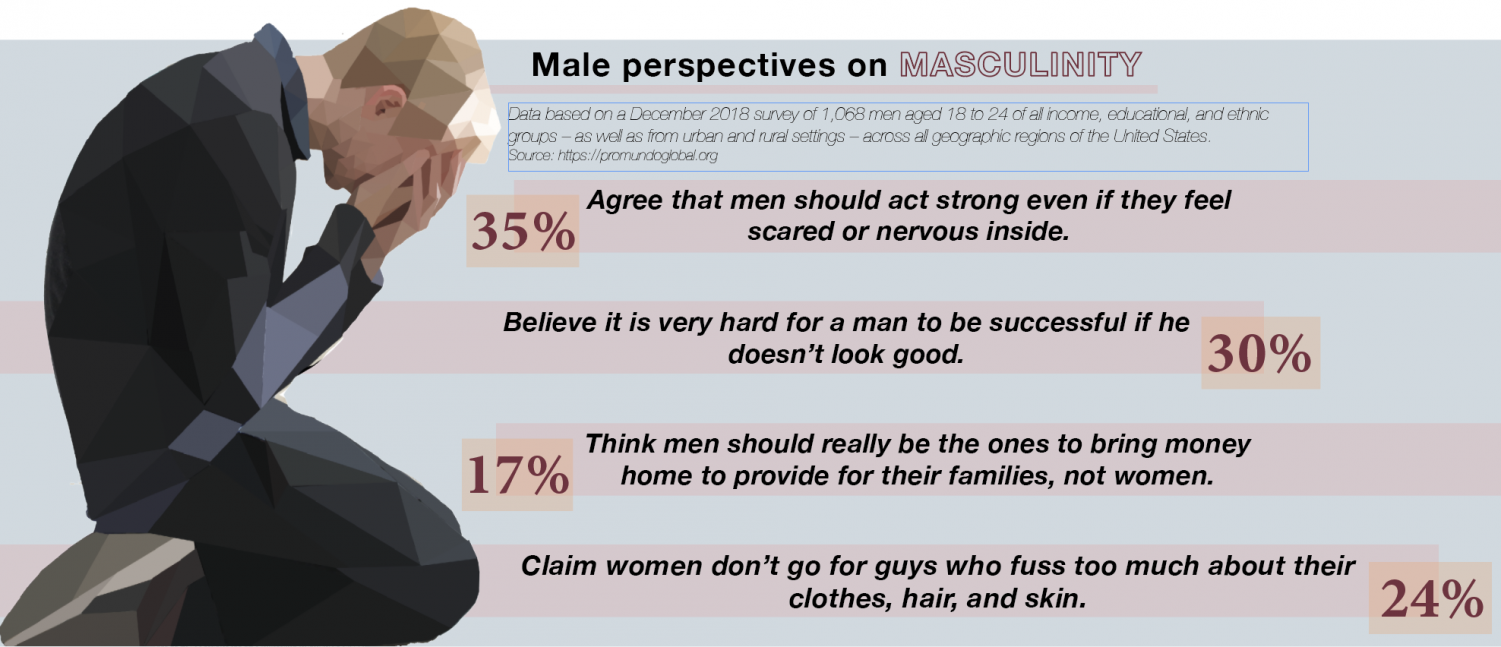

Societal stigma surrounding stereotypical male behavior challenges the definition of masculinity

On the brink of a new decade, traditional gender norms may be regarded as having undergone major progressions in the past ten years. While there continues to be a divide between those who embrace new liberal gender ideologies and those who prefer the normative, the evolving state of gender expectations continues in prevalence.

An issue associated with modern analysis of how gender roles affect those placed into them is toxic masculinity, which English teacher Matt Flickinger defines as a behavior or expectation having to do with traditional ideals of maleness that can be in any way identified as damaging.

“I teach a class on gender, race and ethnicity,” Flickinger said. “As part of the curriculum, we get into a lot of discussion where toxicity is deconstructed, but it also reveals itself in the discussions that we have in the form of privilege where the boys tend to justify their actions or their humor in some way.”

Kara Jackson, who is an on-campus licensed specialist in school psychology, emphasized the objective divide between toxic and non-toxic masculinity, stating that the perception of toxicity within the individual is a contributing factor.

“There’s traditional masculine and feminine traits but at what point does it become toxic?” Jackson said. “I think it kind of depends on the individuals and what they’re experiencing. I’m sure everyone has different experiences and some people may not really see it as a problem and some people could be more affected by it.”

According to Flickinger, a key aspect of toxic masculinity is the need for males to put on some sort of facade. Additionally, he notes that there are numerous factors contributing to the learned toxic behaviors which support the idea of males adopting pseudo-masculine traits.

“I think South Austin has a lot of worship towards things that tend to breed toxic masculinity,” Flickinger said. “Conventional Christianity being one of them, as well as football. What makes a man in this area is often affiliated with the expectations that certain sports and certain behaviors manifest. I think it has to do with some sort of hardwired southern value aspect.”

Sophomore Trey Brown defines toxic masculinity as the tendency for males to suppress their emotions to appear more manly or to give them a sense of self-identity. As a baseball player, he commented on the connection between expectations in athletics and the masculine behaviors expressed by male athletes.

“Especially for athletes, there’s a general idea of us all being meat-heads who only lift weights,” Brown said. “As an athletic jock, you’re supposed to fit a certain stereotype as this big strong guy who doesn’t have emotions or a big dumb brute who’s just goes up there and swings a bat or scores touchdowns.”

In regards to the methods used in athletics to motivate and encourage players, Jackson understands the intention however believes that the expectations in the dynamics between coach and player may be detrimental to physical and emotional health.

“I can see how coaches use strategies to toughen players and get them back out onto the field to focus on winning a game, which could be used in a positive way to motivate athletes, but I can also see how that could be harmful,” Jackson said. “Check on how someone’s feeling and if they’re like mentally ready to get back into the game.”

As stated by Flickinger, the inflated sense of entitlement perceived from athletics can contribute to the manifestation of toxic traits and mindsets within males in a society that can idolize hyper-masculine athletic behavior.

“Most often in these positions of power dynamics, there’s a sense of entitlement to male athletes that provide them with some false ego of bravado,” Flickinger said. “I think we often see it in some of our rituals, like pep rallies.”

While the idea of a ‘jock’ still remains prevalent, Brown asserts that athletes like himself no longer need to fit a certain mold of traditional stereotypes.

“You could say that you’re still a jock, but it’s definitely not as controlled as it used to be. There’s opportunities to be more than just a jock,” Brown said.

While masculinity and femininity can be viewed as polar opposites, Co-President of the Female Empowerment and Motivation Club senior Katie Cole expressed the necessity to discuss the two in relation to each other, since some believe men who express their feelings are feminine or spineless.

“Young men feel the need to treat women a certain way because they don’t want to be seen as gay or weak,” Cole said. “They feel the need to be strong and athletic and be a stereotype because if not then they’re deemed weak and bullied for it sometimes.”

Flickinger related the physical strength differences between men and women, commenting that there is no longer a need to seriously distinguish genders based on physical prowess in modern times.

“The male race is stronger so they were physically responsible for so much,” Flickinger said. “Now we get into gray areas when we talk about the nature of strength. I would say that the strongest people that I know are females, because they’re much better with their emotions. I think that there’s power dynamics at play now and to continue in that mindset is ridiculous in 2019.”

Communication is another subset of limitations associated with toxic masculinity, which Jackson thinks can be overcome through practice of more open and accepting dialogue for males in regards to expressing more personal feelings.

“If your friends aren’t being vulnerable with you, then you’re less likely to be vulnerable as well,” Jackson said. “Typically, when it’s more accepted for you to talk about your feelings and talk about the challenges that you have, the more you talk about it. Opening up that dialogue and being the first one to be vulnerable is the right way to go.”

For those struggling with toxic masculinity issues, Cole would tell them that even though they may believe that there is strength in silence, there is even more strength in opening up and being comfortable sharing things with others.

“I feel like for girls, it’s more socially accepted and kind of expected that you’re going to talk through things,” Cole said. “I definitely feel like that’s true in high school, where girls feel a lot more comfortable talking about feelings with their friends.”

Reminiscing on the difference in mindset between himself and his centrist English professor father, whose “old world” ideals clashed with his own, Flickinger expressed the evolution of generational perspectives regarding masculinity and the expected roles of males.

“I think it does come down to a generational thing,” Flickinger said. “But it also comes down to religion and continuing to hold on to these old world ideas because it’s difficult to let go. For some people to change, I think it takes experience and a willingness and openness to know that maybe there isn’t a direct answer.”

Based on prior experiences working with families of struggling students, Jackson has identified that fathers sometimes realize that the masculine expectations they project on this sons can negatively affect their student performance and emotional expression.

“I’ll be having a meeting with parents and dads sometimes recognize when maybe they’ve passed along certain ideas to their kids,” Jackson said. “But I think it does depend on the relationship between the parents and the kids. When parents can be more vulnerable with their kids, then that shows the kids that they can be vulnerable too.”

Senior Trey Campsmith expressed that the expectations set by parents are not always detrimental, since he believes his father has the best intentions in encouraging him to excel in the activities that he is involved in.

“There’s always expectations that both your parents set for you,” Campsmith said. “Your dad wanting you to do good in school and do good in sports and everything, but I think my dad wants what’s best for me. I don’t think he’s pushing any expectations for his own benefit or for what he wants for me, I think he wants what’s best for me and knows what I want in life.”

Despite the immense issue of toxic masculinity affecting expectations of males, Flickinger observes male students in his classes who are becoming more open and willing to talk about toxic behaviors that they may have and the repercussions associated with them.

“I’m seeing signs of hope,” Flickinger said. “I have had many interactions with boys who are willing to identify that perhaps their behavior is a result of some stuff that’s been ingrained in them that is potentially toxic. I’ve also had students who, through the discussion of these kinds of behaviors, reflect change a lot of their behaviors.”

To Jackson, a possible solution to issues of toxic masculinity in teenagers lies in communication, which she believes can open up deeper conversations relating to problems of suppression in males.

“A lot of teenagers in general, but especially boys more often than girls, have a harder time accepting that they need help or recognizing that they need to seek it out,” Jackson said. “If you’re not seeking help when you need it, then that’s only going to exacerbate the problems that you’re facing. If you don’t ask for help as much or accept weaknesses, that can lead to emotional problems.”

Campsmith challenges the limited perspective that come with problems of toxic masculinity. He believes that labeling masculinity as “toxic” is ultimately detrimental to how people perceive masculinity and masculine traits.

“I don’t think masculinity is inherently a bad thing,” Campsmith said. “To label it toxic is kind of a misconception, because when people hear toxic masculinity they start to think of all masculinity being toxic. I just don’t think that’s right, not all masculinity is toxic.”